Popular Articles

Discover the Historical Events and Famous People Born on May 9

May 9 is a day filled with important historical events and the birthdays of many famous people. From the world’s...

What’s in Your Zodiac If You Born on May 9 [Life, Career, Relationship]

The May 9 Zodiac sign is Taurus. Venus and Saturn are the planets that rule you. The second sign of...

An In Detail Case Study of Pikruos With It’s Benefits and Success Story

Running a business is hard. You might feel lost or overwhelmed by the choices out there. Pikruos is here to...

Sonny Side’s Wife Still a Mystery to the Fans [What We Know So Far]

In a world brimming with love stories, the tale of Sonny Side and his wife stands out, shrouded in mystery...

A Complete Image Guide and User Experience on SimpCityForum in 2024

Are you feeling lost in the vast world of SimpCityForum? You’re not alone. Many users find it tough to get...

Tiffany Pesci Age, Height, Wiki, Instagram, Net Worth, and More in 2024

Finding information online can sometimes feel like looking for a needle in a haystack. With so much out there, it’s...

Latest Articles

Miss Teen USA UmaSofia Srivastava Resigns, Days After Miss USA

UmaSofia Srivastava, who made history last fall as the first Mexican-Indian Miss Teen USA, announced her decision to relinquish her...

Harry Kane Distraught After Bayern’s Thrilling Champions League Loss to Real Madrid

Harry Kane, the talented striker known for his goal-scoring prowess, was visibly devastated following Bayern Munich’s heartbreaking Champions League defeat...

OpenAI Explores Ethical AI-Generated Adult Content Creation

On Wednesday, OpenAI released draft documentation outlining its vision for the behavior of its AI technologies, including ChatGPT. The lengthy...

Sanjiv Goenka Criticizes KL Rahul Publicly After Defeat Against SRH

The Lucknow Super Giants (LSG) suffered a devastating 10-wicket loss against the Sunrisers Hyderabad (SRH) on May 8, 2023, at...

Discover the Historical Events and Famous People Born on May 9

May 9 is a day filled with important historical events and the birthdays of many famous people. From the world’s...

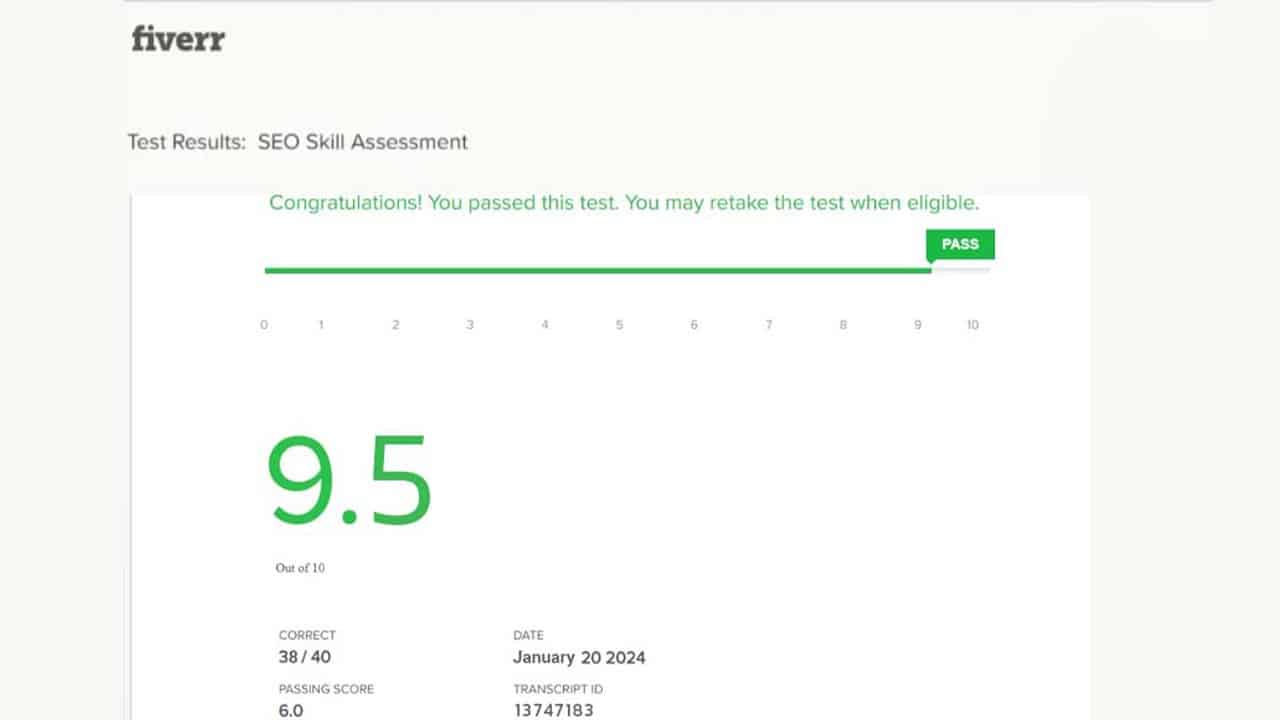

Fiverr SEO Skill Assessment Test Answers 2024 [95% Score Guaranteed]

Here, I’ve shared Fiverr SEO skill assessment test questions and answers in 2024. I’m ensuring that you will get a...