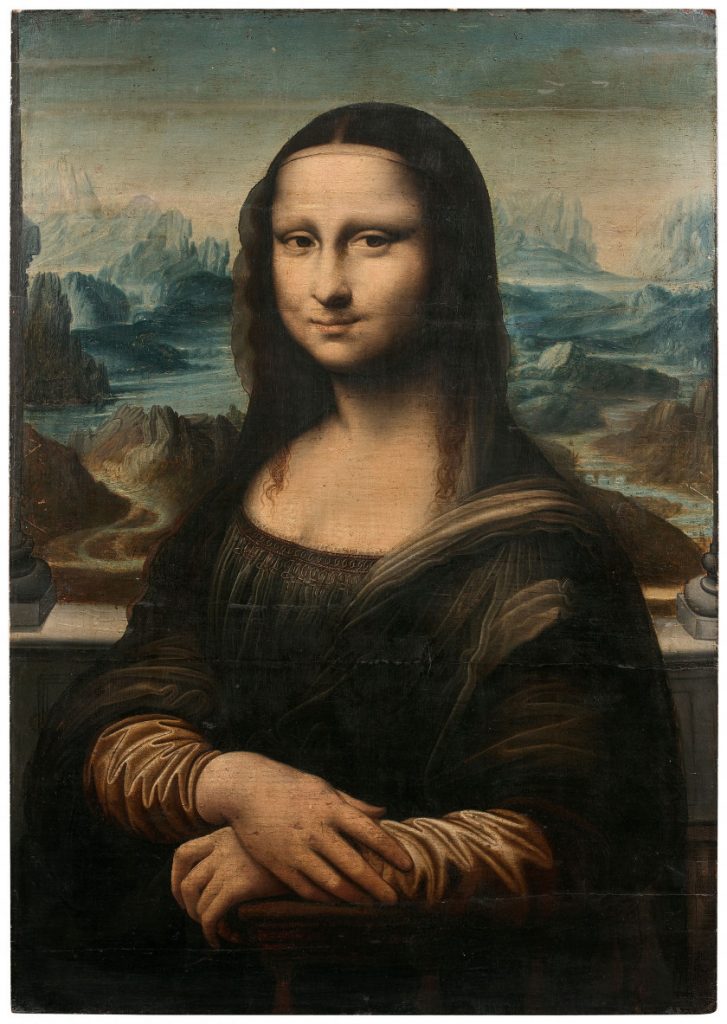

In 2012, UNESCO’s General Conference established April 15 as World Art Day 2022 to honor and commemorate the birthday of the greatest artist of all time, Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci. On this day every year, a festival is held to encourage the creation, distribution, and enjoyment of art.

Individuals all around the world benefit from art’s encouragement of creativity, innovation, and cultural diversity, and it plays an important role in information exchange, curiosity, and debate. These are qualities that art has always had and will continue to have if conditions that protect artists and artistic freedoms are maintained.

WHY IS THE APRIL 15 CELEBRATED As WORLD ART DAY?

The date of April 15 was chosen since it was Leonardo da Vinci’s birthday, and he is regarded as one of history’s most renowned artists. Leonardo da Vinci has become a symbol of fraternity, peace, and freedom of speech.

SIGNIFICANCE AND CELEBRATIONS FOR WORLD ART DAY 2022

Around the globe, World Art Day 2022 April 15 is filled with cultural activities, conferences, exhibitions, and workshops. Anyone should learn an artistic endeavor for a variety of reasons.

Some of the advantages that art has to provide are as follows:

- Art piques one’s interest in learning and becoming creative.

- Concentration, hand-eye coordination, and problem-solving skills all improve with art.

- It boosts emotional intelligence and makes it easier to articulate difficult emotions.

- By breaking down racial prejudices and religious barriers, art aids in the formation of communities.

- It improves your general health, raises your self-esteem, and motivates you.

- Art stimulates the senses and allows people to view things differently.

For many people, art is a popular hobby. Artists earn a living for some individuals. According to the National Endowment for the Arts, there are over 2 million professional artists in the United States. A substantial percentage of this category consists of fashion designers, flower designers, and graphic artists. Writers, animators, and architects account for a smaller proportion of the artist community.

Apart from this, if you are interested; you can also read Entertainment, Numerology, Tech, and Health-related articles here:

7starhd, Movieswood, How to Remove Bookmarks on Mac, Outer Banks Season 4, How to block a website on Chrome, How to watch NFL games for free, DesireMovies, How to watch NFL games without cable, How to unlock iPhone, How to cancel ESPN+, How to turn on Bluetooth on Windows 10, Outer Banks Season 3, 6streams, 4Anime, Moviesflix, 123MKV, MasterAnime, Buffstreams, GoMovies, VIPLeague, How to Play Music in Discord, Vampires Diaries Season 9, Homeland Season 9, Brent Rivera Net Worth, PDFDrive, SmallPDF, Squid Game Season 2, Knightfall Season 3, Crackstream, Kung Fu Panda 4,

1616 Angel Number, 333 Angel Number, 666 Angel Number, 777 Angel Number, 444 angel number, Bruno Mars net worth, KissAnime, Jim Carrey net worth, Bollyshare, Afdah, Prabhas Wife Name, Project Free TV, Kissasian, Mangago, Kickassanime, Moviezwap, Jio Rockers, Dramacool, M4uHD, Hip Dips, M4ufree, Fiverr English Test Answers, NBAstreamsXYZ, Highest Paid CEO, The 100 season 8, and F95Zone.

Thanks for your time. Keep reading!